“The appearance of antisemitism in a culture is the first symptom of a disease, the early warning sign of collective breakdown,” according to Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks. More evidence to prove his theory came last Friday in the form of a jury verdict of $11M against Oberlin College in Gibson’s Bakery v. Oberlin College.

In 2016, Oberlin students protested a family-owned bakery after its cashier attempted to stop a student of color from shoplifting. It was the allegations of racism and racial profiling made at this protest, allegedly with support from the College administration, and which proved to be without foundation, that led to last week’s $11M verdict. (For more on the trial and what led to it, see the extensive coverage on the Legal Insurrection blog.) The possibility that the student was in fact guilty was not something either the student body, or administrators, were willing or able to entertain.

Rabbi Sacks has also said that antisemitism “reduces complex problems to simplicities. It divides the world into black and white, seeing all the fault on one side and all the victimhood on the other.” So it was with the Gibson’s case, a case which, on the surface, had nothing to do with antisemitism, but which mimicked this mindset.

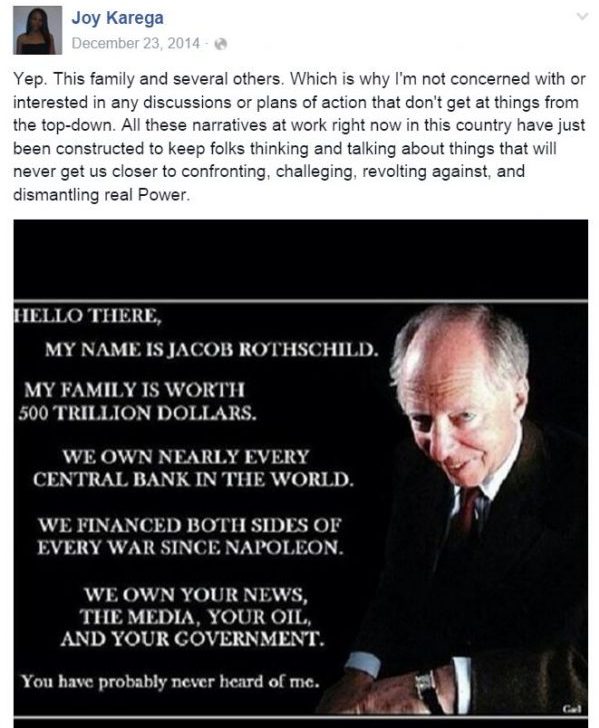

Oberlin is the school that hired, and first defended (before ultimately firing), Professor Joy Karega, who wrote on Facebook that the Mossad was behind the 2015 attack on the offices of Charlie Hebdo in Paris, that “Israeli and Zionist Jews” were responsible for the attack on the World Trade Center, and that Jacob Rothschild and his family “financed both sides of every war since Napoleon,” and “own your news, the media, your oil and your government.” Not coincidentally, she also claimed after Hurricane Sandy that the weather had been “weaponized.” Oberlin is the school where, on Rosh HaShana in 2014, students posted a huge banner, designed to appear as if it were written with blood, saying that tuition money funds genocide committed by Israel. It’s the school at which, as far back as the early 1990’s, when I was a student there, the simplistic and western idea that those with white skin were always oppressors and those with dark skin always oppressed was misapplied to the Israeli-Arab conflict, erasing the history of centuries oppression of Jews in the Middle East and Europe.

While the Gibson’s verdict has been widely covered in the media, most of the coverage overlooks the connection between antisemitism at the school and the Gibson’s case. But Meredith Raimondo, the Dean who was at the center of the Gibson’s controversy, has previously featured material that many would consider antisemitic in courses that she taught. In 2016, when she was promoted to Dean, The Tower reported that Raimondo’s online syllabi had included work by Joseph Massad, Lisa Duggan, Judith Butler, and Jasbir Puar.

The syllabus for Raimondo’s 2013 seminar on “Transnational Sexualities” included a paper by Puar titled “Citation and Censorship: The Politics of Talking About the Sexual Politics of Israel.” Puar’s piece . . . features critiques of what she calls Israel’s practice of “pinkwashing,” its ostensible efforts to distract from “its repressive actions toward Palestine” by emphasizing its progressive policies towards LGBTQ individuals. The paper concludes with a reflection on “the ways in which accusations of ‘anti-Semitism’ function in academic and activist contexts to suppress critiques of the implicit nationalism within Israeli sexual politics.”

What does this say about the Dean’s critical thinking skills?

To return once more to Rabbi Sacks, “the hate that begins with Jews never ends with Jews. Antisemitism is only secondarily about Jews. Primarily it is about the failure of groups to accept responsibility for their own failures, and to build their own future by their own endeavours.”

In August of 2016 a very prescient Oberlin professor sent an email to Oberlin Alums for Campus Fairness President Melissa Landa, in which the professor declined to assist Oberlin ACF in holding a symposium on antisemitism at the school. In this email, the professor wrote, “we here at Oberlin College are on the brink of hysteria that, should it truly get going, will not end until literal harm is done.” That is exactly what happened, only five months later, in November of that year.

After three years of fighting antisemitism at the school with Oberlin ACF, it gives me no pleasure to say that the school’s reputation probably won’t recover from this for a long time, if ever. Oberlin was once a great institution – it was one of the first racially integrated and coeducational schools in the country, and the town was once a stop on the Underground Railroad. That was one of the reasons I chose it. But if, as Tablet magazine editor Alana Newhouse once said, antisemitism is a “brain-eating disease,” then Oberlin College is this disease’s latest victim.

Contributed by Assistant Director of CAMERA’s Media Response Team Karen Bekker.