In recent decades, universities across the UK have made tremendous strides towards inclusion and anti-discrimination policies which aim to protect minority group students from being alienated or subject to abuse. Yet, in a tale as old as time, the needs of Jewish students have been overlooked and ignored by university bodies.

An inquiry made in late August by Campaign Against Antisemitism has revealed that 43 British universities have not yet adopted – or have outright rejected – the definition of antisemitism drafted by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA). This comes in spite of its formal adoption by the British government in December 2016.

In a 2018 parliamentary debate, then-Prime Minister Theresa May said: “We should all sign up, as the Conservative party has, to the definition of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance and all its annexes.” That same year, Labour Party leader, Sir Keir Starmer, also urged his Labour colleagues to “get to a position where we are supporting the full definition” of antisemitism outlined by the IHRA.

Why then do universities across the UK continue to reject the IHRA definition? According to a February 2021 report by the Union of Colleges and Universities (UCU) at University College London (UCL), the IHRA definition “presents identifiable and serious risks to the academic freedom of staff and freedom of expression” within college campuses.

Such criticisms lack any real argumentative substance. In July 2017, legal experts Lord David Wolfson KC and Jeremy Brier KC published a nine-page opinion which stated, in no unclear terms: “There is no danger or disadvantage for public bodies or universities in adopting this Definition.”

While UCL decided to retain the definition, UCU’s report prompted waves of anti-IHRA debate within the Academic Board. The incessant bickering forced Jewish students to fend for themselves against antisemitism on campus, with some allegedly accusing them of “Zionist plotting” and telling them that “Hitler was right”. Such actions came in spite of UCL Provost Michael Spence’s May 2021 affirmation that “abuse, racism and hate speech have no place here [at UCL].”

Given that the IHRA definition includes additional identifiers of antisemitism relating to the Jewish relationship with the State of Israel, the report identified two groups who would be most affected: those teaching about Israeli history, and those whose “national identity” is at odds with Israel. A number of Levantine nationalities – “Palestinian, Jordanian, Egyptian, [and] Lebanese” – were cited as examples.

The IHRA definition stipulates that using well-established antisemitic tropes, accusations of inherent racism in the quest for a Jewish state and Holocaust comparisons in discussions about Israel’s actions all constitute antisemitism. It does not characterise Palestinian claims to collective self-determination or criticism of Israeli government policies towards Palestinian Arabs as antisemitic. The UCU’s report characterised IHRA as an attempt to prohibit statements critical of Israel. This appears to be a severe misrepresentation of IHRA’s true nature and grossly undermines initiatives to combat antisemitism.

The report further argued that the IHRA definition “could be seen as institutionally racist” against those of Palestinian descent, notwithstanding the fact that the term “Palestinian” has been used throughout history to refer to different ethnicities and doesn’t necessarily apply itself only to Arabs. IHRA makes no mention of Palestinians, nor of any people who historically have experienced conflict with Israel. On the contrary, it clearly states that “criticism of Israel similar to that levelled against any other country cannot be regarded as antisemitic”. In suggesting that IHRA’s mission is to stamp out Palestinian voices and discriminate against “the protected characteristic of the Palestinian nationality”, the UCU’s report demonstrates a clear and deeply problematic misreading of IHRA’s fight against rising antisemitism.

The UCU’s convoluted anti-IHRA statements are deeply offensive to many, and have since proved to be factually incorrect. A 2023 investigation by the Parliamentary Task Force on Antisemitism in Higher Education objectively disproves their claims. Of the 56 universities surveyed, none “knew of or could provide a single example in which the IHRA definition had in any way restricted freedom of speech or academic research, or where its adoption had chilled academic freedom, research or freedom of expression”.

However, this has not convinced academic boards everywhere to begin implementing the IHRA definition into their practices. The debates at UCL have inspired other British universities to reject the definition, such as the University of Brighton, which claims to “[support] the diverse demographic of students and staff” across campus. Yet, the refusal to adopt IHRA suggests that some UK universities are simply uninterested in extending that same support system to Jewish students.

Some might recall the insight I shared with the Jewish News Syndicate (JNS) last June surrounding the parliamentary report cited above. As mentioned in the article, I came face-to-face with antisemitic harassment when other students revealed my Zionist stance to an online group chat. Following the incident, I was referred to an internal complaints team. After a lengthy investigation, they eventually issued misconduct charges against some of the students involved.

Had King’s College London (KCL) not been one of the universities to adopt and implement IHRA into disciplinary policy, this kind of vitriol would potentially have flown under the radar. Even at universities which commit to IHRA, such incidents can occur.

Aside from academic organisations such as the UCU, decisions from universities to adopt the IHRA definition has caused discontent among some student groups. Societies on campus with a history of anti-Israel positions now lament the revocation of their carte blanche to use Israel as a stick with which to beat Jews.

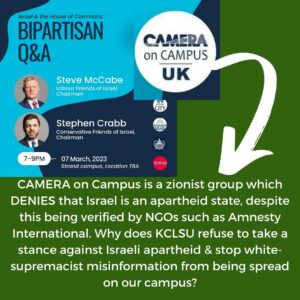

A prime example of such behaviour has been demonstrated by Liberate KCL, a society at King’s which “seeks to build a grassroots liberation movement”. In March 2023, the KCL Israel Society (in conjunction with CAMERA On Campus) planned to host the Chairmen of both Conservative and Labour Friends of Israel to discuss Israel-UK relations at a bipartisan level. Liberate KCL protested the event until it was eventually cancelled due to security concerns. In a since-deleted Instagram post dated 6 March 2023, the group referred to the event as an attempt to deny Israeli apartheid and spread “white-supremacist misinformation”.

I immediately took to the comment section to criticise the post as not only deeply insulting to the millions of Israelis with ancestors who fled the white supremacy of the Nazi Holocaust, but also in flagrant violation of the IHRA definition which KCL has adopted. In response, they accused me of “attempting to weaponise a highly political and flawed definition of antisemitism in order to silence criticism of Israeli Apartheid and the racist Zionist project”. Such accusations constitute a variation of the Livingstone Formula – the idea that Jews disingenuously cry antisemitism in order to silence anti-Israel voices. The post was later deleted, and I have since been blocked.

Ironically, Liberate KCL’s manifesto outlines how it will “represent marginalised students”. They have done no such thing when it comes to Jews. This group, along with the rest of those who stand against IHRA, are fighting a losing battle for a blatantly wrong cause.

In universities where the definition hasn’t been implemented into official policy, the impacts of anti-Zionism on Jewish campus life can be far more damaging. In March 2023, the Palestine Society at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) University of London shared a quote by Lebanese religious extremist Hassan Nasrallah, the Secretary-General of Hizballah, via Instagram.

The quote referred to ongoing political instabilities in Israel as “the end of the Zionist entity” – in effect, a call for the destruction of Israel. Such an occurrence would, at the very least, leave Israel’s 6.9 million Jews and 1.6 million Arabs stateless. SOAS took no action. This comes in spite of the fact that Hizballah’s military wing has been designated as a terrorist group by the UK government since 2008, later proscribed in full in February 2019.

Needless to say, it seems increasingly clear that resisting IHRA helps no one, least of all Jewish students. Of the 43 universities who have refused its implementation, those with appalling records when it comes to antisemitism should consider IHRA a necessary antidote to the poison they’ve helped to spread. University-related antisemitic incidents have increased by 22% since the 2018-2020 academic period, and this trend shows no signs of slowing down. Jews deserve as many protections and as much understanding as is given to other minority groups, and this is simply not the case in universities today.

This article was originally published in ROAR, the campus paper for the King’s College, London (KCL).