Miko Peled, a critic of Israeli policies, was scheduled to come to campus on September 20. He and I agree on little — we disagree on almost everything, actually — but I try to open myself to dialogue. Peled was advertised as a human rights activist, and I looked forward to attending his lecture until members of the Princeton community began to point out his anti-Semitic tweets. Facebook blew up, and Peled was disinvited.

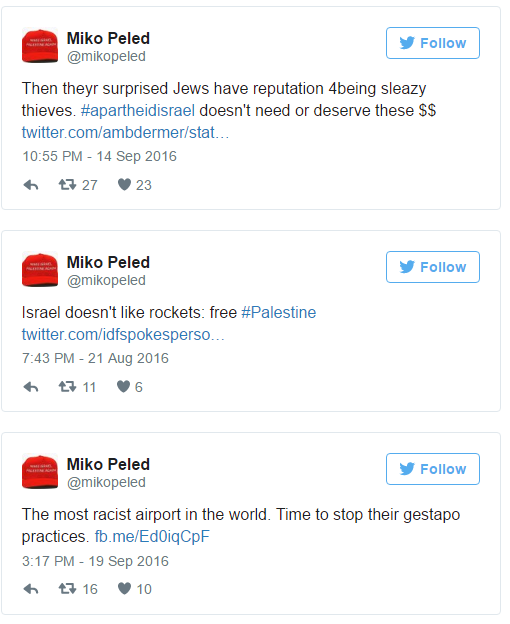

The tweet that caused the cancellation was “then theyr surprised Jews have reputation 4being sleazy thieves. #apartheidisrael doesn’t need or deserve these $$.” It is not wholly uncharacteristic of Peled’s Twitter feed. Because such bigotry is unacceptable for a speaker who claims to defend human rights, students made the right choice in rejecting his voice — and Twitter could learn from their example.

About 20,000 anti-Semitic tweets are directed at Jewish journalists every year — including me. Every time I open Twitter, I find tweets telling me to “go die, kike.” It’s depressing to find all the anti-Semites, bigots, and neo-Nazis gather in one place.

Many of these anti-Semitic Tweets come from the alt right; many come from those who allow their views on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to degenerate into anti-Semitism. The Internet does fall under laws of free speech, but Twitter’s terms of use ban “hateful conduct.” Nevertheless, the site has neglected to address the problem, responding that users themselves are responsible for their Tweets. Twitter users are indeed responsible for their statements — but Twitter is setting a noxious precedent in giving a voice to such anti-Semitic bigots.

Twitter has a department for monitoring posts flagged as containing “hateful language,” but it rarely deletes anti-Semitic tweets. Twitter should establish a clear definition of what constitutes “hateful language” and what constitutes free speech. Staff can then root out anti-Semitism and other forms of bigotry and racism, just like we did at Princeton.

Twitter is not too different from Drew University, which tolerated Peled and his anti-Semitism in the form of “criticism of Israel.” Drew encourages inclusivity and stands opposed to discriminatory language, but in letting Peled speak, it acted very much like Twitter. No university with a true commitment to inclusivity brings a bigot to campus in the context of his human rights expertise.

Unlike the students at Drew University, students at Princeton canceled Peled’s talk. I was proud of them for standing up to anti-Semitism masked as criticism. They instead seek to foster genuine dialogue about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict that doesn’t stoop to the blatant anti-Semitism that rears its ugly head all too often in that conversation. I was proud of Princeton for allowing both sides to debate, without fueling racial or religion-based discrimination.

Discussions about Israel should be encouraged, both on the Internet and in person. A healthy dialogue is necessary for a strong Princeton intellectual community. But this community should not — and, as we have seen, will not — tolerate any discussion of Israel that becomes anti-Semitic. Unfortunately, on an increasing number of campuses across America, the dialogue that I mentioned previously does not exist, and anti-Semitism caused by degeneration of such “dialogue” is a real fear for many students.

Universities across America stress their commitment to diversity and respect — but invitations of anti-Semitic speakers like Peled prevents institutions and students from taking them seriously. While discussion is necessary, anti-Semitism is not, and I am glad to see that the students of this intellectual community recognize that. The canceling of Miko Peled’s talk was a testament to the values we are proud to uphold — and the values Twitter could learn from.

Originally published at The Daily Princetonian

Contributed by Leora Eisenberg, CAMERA Fellow at Princeton University